Once upon a time, long long ago, America and Russia were not only true allies but—believe it or not—actual friends. Here's a short list of historical events – any resemblance to contemporary events is purely coincidental.

AMERICA’S INDEPENDENCE

Among the European great powers of the day, Tsarist Russia played no small role in helping the fighters for American independence—mainly because it wanted to stick a finger in Britain’s eye. You know, the usual dynastic drama of Europe’s incestuous blue-blooded imperial families: torn linens, jealous cousins and other royal family feuds.

In the 18th century, Catherine the Great rather “politely ignored” Britain’s requests that she send her navy and 20,000 soldiers to help put down the “moderately democratic rebel revolutionaries” in the American colonies. Instead, she coolly replied that she might consider helping—but only if Britain handed her the Spanish island of Menorca in the Balearics. And even after this "impossible offer" was given by the British king, she simply found another excuse to retain her official policy of armed neutrality in relation to the 13 former colonies.

Catherine the Great (1729-1796)

1812

Then came the Anglo-American War of 1812, and again the Russians stepped in to help the burdening Americans.

The British scored a string of victories, famously torching the White House (hence the story of why it’s white). But Tsar Alexander I didn’t want British troops tied down in America for too long—Russia and Britain were allies against Napoleon, and another clash with France was looming. Besides, Russia valued America as a trading partner and a friend.

So Alexander I offered to mediate. President Madison and his delegation travelled to St. Petersburg for negotiations, and despite the British side boycotting the negotiations, his mediation helped produce the 1814 Treaty of Ghent, restoring the pre-1812 status quo.

THE CRIMEAN WAR – WORLD WAR ZERO

During the Crimean War (1853–56), while Russia fought a coalition of Britain, France and the Ottomans, the United States stayed neutral—and at times quietly helped Russia. American ships supplied food and water to Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky during the British-French blockade of Russia’s Pacific coast, and American shipyards even built naval and civilian vessels for Russia.

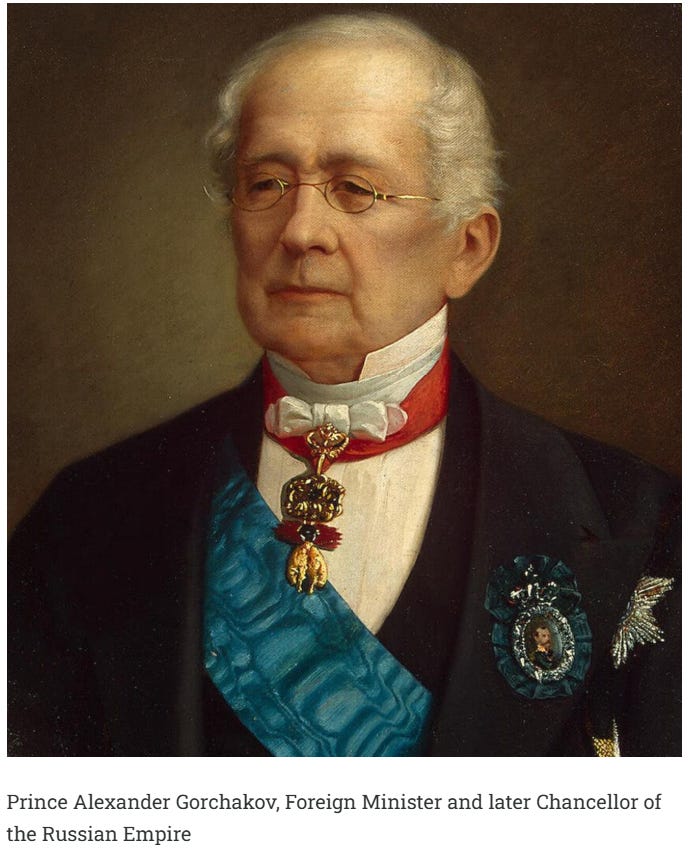

In 1856, Russian foreign minister Prince Alexander Gorchakov wrote:

"The sympathy of the American nation for us has not weakened throughout the war, and America has provided us directly or indirectly more services than could be expected from a power that maintains strict neutrality." In addition, Gorchakov pointed out that "Russia's policy toward the United States is definite and will not change depending on the course of any other state. Above all we wish to preserve the American Union as an undivided nation... Russia has been offered to participate in plans for an intervention. Russia will reject any such proposals."

CIVIL WAR—SLAVERY, TEXTILES AND THE POLES

Friendly ties deepened further thanks to Abraham Lincoln’s push to abolish slavery and Tsar Alexander II’s emancipation of the serfs in 1861. Inspired by Russia, Lincoln demanded an end to slavery in the American South, which helped trigger the Civil War (1861–65).

When Lincoln issued the "Emancipation Proclamation" in 1863, he even invoked the example of “the absolutist ruler of the Russian Empire.”

Meanwhile, Russia’s reputation was shaky after losing the Crimean War. In 1863, when a Polish uprising broke out against Russian rule, Britain and France wanted Europe to recognize Polish independence. At the same time, London and Paris considered intervening in America’s Civil War.

Britain recognized the Confederacy as a belligerent power and was prepared to back it militarily—the South’s cotton, grown by slave labour, was vital for Britain’s textile industry. In June 1863, Britain sent five warships to Canada’s Pacific port of Esquimalt. The Union forces had no navy to counter them.

France had its own adventure going in Mexico—its army took Mexico City that June—and was secretly shipping arms to the Confederacy.

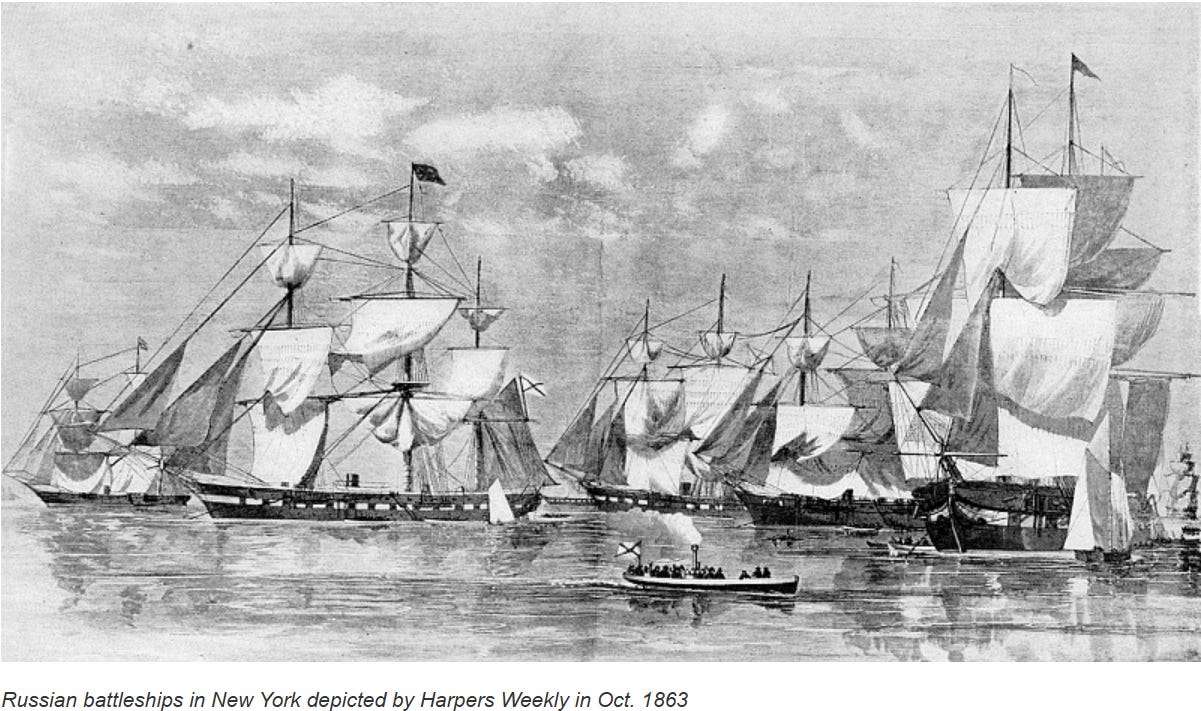

Enter Russia: On June 25, 1863, Alexander II secretly dispatched his fleets under two rear admirals to the U.S. coast.

“The mere presence of the Russian navy was enough for England and France to realize that Russia was prepared to shield the United States from foreign intervention,” U.S. Secretary of State William Seward wrote at the time.

The Russian fleet never clashed with enemy ships, but Admiral Popov’s standing order was clear: “If you meet them—engage.” Confederate weak fleet on the Pacific coast wisely kept their distance.

Between 1863 and 1864, the Russian fleet toured Cuba, Honolulu, Jamaica, Hawaii and Alaska. In New York, November 1863, thousands attended a gala for the Russian sailors. Lincoln himself welcomed Admiral Lesovsky and his officers to the White House.

While the Russian navy lingered in American waters, neither Britain nor France dared attack the Union nor challenge Russia in Poland. By June 1864, the Polish uprising had been crushed, and Russia’s naval gambit had succeeded perfectly.

Of course, Russia’s fleet could never have defeated the combined navies of France and Britain, but it could have blocked vital shipping routes—already as critical then as they are today.

THE "STRATEGIC" SALE OF ALASKA

As early as 1859, Russian Empire, broke after the Crimean War, offered to sell Alaska, its North American colony, to the U.S. The territory was costly to defend, far from Russia’s European heartland, and Britain had its eye on it, posing a strategic threat to both United States and Russia.

The sale was delayed by the Civil War but finally went through in 1867: the U.S. bought Alaska for $7.2 million—roughly $150 million in today’s money, a bargain. At first, Americans derided the deal as “Seward’s Folly,” but after gold was discovered in Alaska thirty years later, they changed their tune.

In those years, U.S.–Russian friendship was at its peak, with rich cultural exchanges.

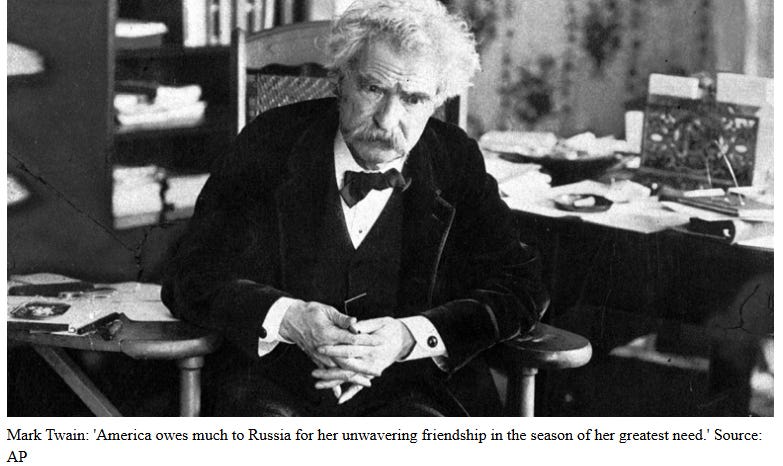

Mark Twain visited Russia and wrote vividly of Odessa, Sevastopol, and Yalta, where Tsar Alexander II hosted him. Twain praised the Tsar’s emancipation reforms and Russia’s aid to America during the Civil War. Privately, though, he lamented not stealing the Tsar’s coat as a souvenir. Twain was, after all, an American—and a very colourful character, to say the least.

Russian aristocrats likewise toured America, feted like celebrities at balls and receptions. Russians were by far the most warmly received foreign visitors in the U.S.

THE COOLING OFF

But then came the pogroms of the late 19th century, and the first cracks in this rosy friendship began to show. Thousands of Russian Jews fled to America, bringing with them bitter memories of tsarist repression. They became some of the fiercest critics of Russia in the New World. Even more detrimental was the famine of 1891–92.

Americans raised massive amounts of aid for starving Russians, but the Russian authorities, to put it mildly, botched distribution. Corrupt officials pocketed much of the aid, and critics in the U.S. (especially those keen on closer ties with Britain) accused Russia of actually exporting grain from famine-stricken areas, claiming the aid wasn’t needed at all.

American media, already privately owned and serving “higher interests”—not yet as bad as today, but close enough—blamed Tsar Alexander III personally for the famine.

Soon after, Washington and powerful financiers like anti-Russian oligarch Jacob Schiff funnelled heavy support to Japan during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904/05. Relations with Russia—America’s oldest and truest friend—were in free fall.

The October Revolution of 1917 finished the job.

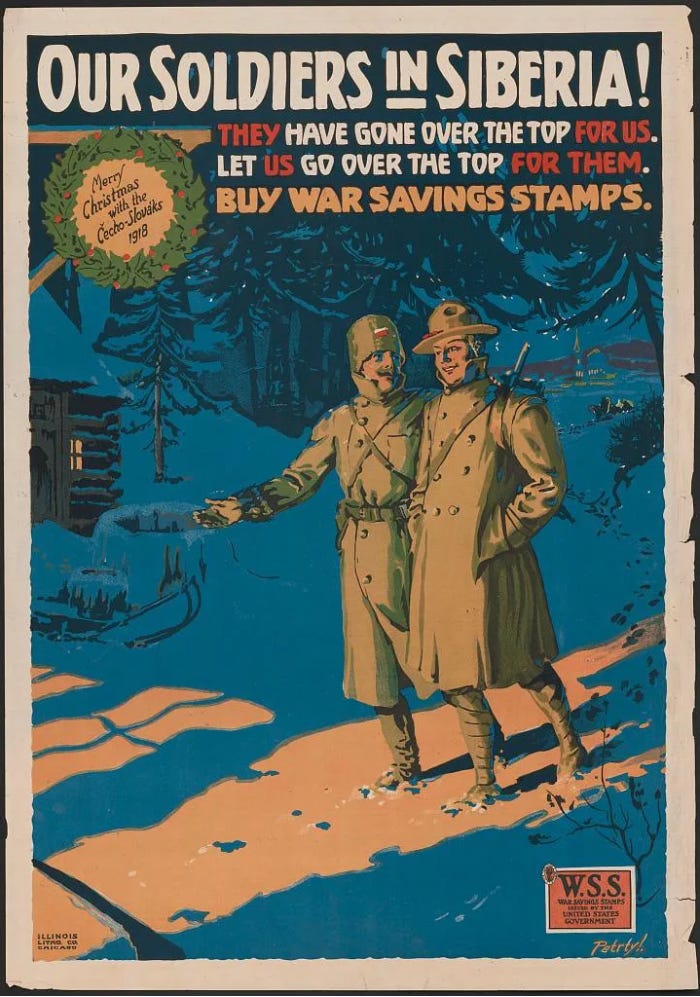

For the first time, America and Russia stood on opposite sides of history, split by the liberal capitalism vs. proletarian socialism chasm: America joined Britain and France in intervening in Russia’s civil war—naturally on the side of the Whites, the so-called “democratic reactionaries.” U.S. troops were even getting lost wandering the Siberian wilderness around Kamchatka.

Though the Soviet victory was clear by 1922, Washington didn’t officially recognize the USSR until 1933.

WW2 AND "MISSION TO MOSCOW"

And yet, with America’s entry into WWII brought a brief, uneasy resurrection of the old alliance—as wars typically tend to rearrange enemies and friends.

And so from 1941 to 1944, America and the Soviets played at being “friends” again—though it was more like a marriage of convenience, and one partner (you know which one, the one immortalized by Anglo-American historians and Hollywood as the “eternal flame and shining light of goodness and distilled virtue”) was already scheming behind the other’s back. Since 1917, the real American endgame had always been regime change in Moscow and the destruction of the “Red Menace” in order to "liberate" its vast natural resources.

A curious artifact of that fleeting wartime “friendship” is the 1943 film "Mission to Moscow", based on the memoirs of U.S. ambassador Joseph E. Davies.

It is one of the very few surviving American films that actually portrays the Soviets in a positive light—a propaganda gem now so awkward it borders on forbidden history.

As for Churchill’s intrigues, British double-dealing before, during, and after the war, America’s own role in the rise of fascism and Nazism in Europe and Japan, and the centuries-old Anglo-American coveting of Russia’s “unfairly enormous” territory and natural wealth—well, no need to waste more words here.

THE “GREAT GAME” REDUX—AND ALASKA 2025

And yet, history is never linear and has no "end", despite the prevailing "neocon historical truths and realities of the World". Alaska once again became the centre-stage of Russo-American relations.

Yesterday’s presidential summit in Alaska publicly hinted—for the first time for most of Western mainstream society—that U.S.–Russian relations may finally be returning to a more logical, historically grounded framework. Of course, if we could set aside a century of deep-rooted propaganda and ideological nonsense, that will slowly but surely revert—for some (USA) more than others (EU)—from an "axiom carved in stone" to more of an "ahistorical guideline".

The American empire, weighed down by the uncovered Dollar IOU's of European-style imperialism, the gargantuan hangover of its “Cold War victory,” and the reckless binge of Wall Street hypercapitalism that hollowed out its own social fabric, seems at last to be slowly circling back to its historical roots.

The goal of the proxy war in Ukraine was never Ukraine itself. As with all proxy wars, the country was merely the tool, the “neutral” stage for a great power clash.

Its origins go back at least to the “Orange Revolution” twenty years ago, and to NATO’s 2008 Bucharest summit, where despite Russian objections, Ukraine and Georgia were offered Membership Action Plans—a veiled invitation to join. Putin had already sounded the alarm a year earlier, in his famous 2007 Munich Security Conference speech—a direct "warning shot" across the bow as a clear answer to Washington’s thrown gauntlet.

NATO’s expansion eastward broke the “gentleman’s agreement” about Europe’s “indivisible security”—the unwritten golden rule of spheres of influence since the Napoleonic wars.

The true aim of America’s gambit, its 21st-century spin on the “Great Game,” wasn’t just regime change in Moscow or a Kremlin “Maidan.” That was a side quest. Of course, Washington would happily seize Russia’s natural wealth outright, but the real decision-makers aren’t as naïve as the theatrical troupe of U.S. politics, which long ago degenerated into a reality show in the style of World Wrestling Entertainment.

The real objective, as in the early 20th century, is economic and strategic dominance over Europe itself—clipping the wings of the Old Continent. A Europe that could slip free of Washington’s grip and revive its old grandeur (say, through a genuinely sovereign EU) would be equally unacceptable to America—the challenged hegemon, and to Russia—the resurgent great power.

A century ago, the U.S. faced a similar financial crunch—astronomical debt, spiralling crises (the Great Depression was but one symptom). Its exit strategy was a global shock: World War II, followed by the Bretton Woods system, which Washington itself later torpedoed in the 1970s, plunging its own economy—and much of the world's—into the spiral of endless debt.

The days of the “First World’s” neocolonial prosperity model are over. Former colonies are asserting economic and strategic independence. The U.S. can’t quit cold turkey—it wouldn’t survive—but once again, the transition will be paid for by Europeans and ordinary Americans. This time, though, under actual fairtrade terms with the global South.

The new mercantilist economic "hegemon" has long since became China.

The military “champion” of the seven billion outside the “Golden billion” is a revived superpower Russia.

And so, behind closed doors, China, the U.S., Russia and India have been negotiating new trade routes (especially through the Arctic), joint exploitation of untouched resources, and ways of “managing” Europe’s half a billion people—and stripping it of its accumulated capital, which besides its workforce is its only remaining asset. In recent months, Washington and Moscow have held especially intensive bilateral talks.

Yesterday in Alaska, Vladimir Putin surely reminded his American hosts of more than one of the historical "alternative truths" recounted here - and no doubt, much was surely also left unsaid. For now.